As we live in an age of nation-states, our world has tied the histories of entire peoples and landscapes to the identity of a single ethnicity in each corner of the world, typically with some form of government made to create laws and institutions to rule in favor of that group. Suppose you live in the United States, for instance. In that case, you will be spending your whole life going to schools with lessons given in the English language, in addition to being taught a history centered around the concept of an “American” identity, almost as if there were no other ways of identifying yourself in the past. Even in regions where exposure to other languages is more common due to sharing borders with varying nationalities, you will still find this more significant emphasis on political powers catering everything to that country’s dominant ethnicity, be it France, England, or Russia.

However, we’re so focused on the identities of a majority and how past events in history played into our political system that we neglect that there were others before us, people with us now, with their own cultures and modes of life foreign to us today. The ghosts of enslaved Africans reawaken with the death of George Floyd, reminding the Western world of its colonial past and giving a voice to the previous and current struggles for the rights of blacks in the West. They cry out for their rights but also sing praises of their empires that have been given little attention by most of the world, such as the African kingdoms of Mali and Ethiopia, pointing frantically that they once had power rivaling others of the world. The once mighty empire of the Assyrians lies in ruins throughout the Middle East; the Assyrians are now a shadow of what they once were. Centuries of assimilation and cultural genocide have contributed heavily to this. Many nomadic cultures are on the verge of cultural destruction, with nomads in countries from Mongolia to even many Middle Eastern countries forced to sacrifice their way of life to find work in the cities.

The question of minority representation is not to say there haven’t been changes for the better within this model for the world’s nations. The United States has been able to make some improvements in its treatment of minorities, such as the abolishing of slavery and Jim Crow laws. Many minorities even pursue the nation-state model to advocate for themselves in a nation-state world. However, I must emphasize that even with the benefits of what’s available now, our problem is that we still haven’t done enough to bring minorities around the world and our backyard to equal footing with us or to take the time to listen to their stories to see how they’re valuable on their terms, not on what we look for out of them. This lack of intent in our mentality has led to the detriment of people we only consider when relevant to our countries’ interests.

The Kurds have had the unfortunate luck of counting among these neglected minorities, suffering the same fate. With their land of Kurdistan split between four countries, Iran, Turkey, Iraq, and Syria, their cultural identity has been the target of assimilation policies and barbarous genocide aimed at their extinction. What the Kurds are going through is one of the many extremes of the monsters that lurk within nation-states concerning their minorities, all done in the name of their respective nationalities. Even in ancient times, it has been like this under varying empires, from the Mesopotamian kingdoms to the Islamic empires.

Despite this, the history of the Kurds and their current struggles for autonomy shows the dignity and honor these people had and continue to have today. From their literary history to their relations with the varying empires, shines a strength of stubborn will to hold on to what they have of their culture and to make themselves significant in the eyes of the giants of the world. As one of their poets, Cegerxwîn, once said of the Kurds in his poem, “Kîme Ez:”

Ez im ew kurdê serhişk û hesin

Iro jî dijmin ji min ditirsin

Bîna barûdê

Kete pozê min

Dixwazim hawîr

Biteqim ji bin

Dîsa wek mêra

Bikevin çîya

Naxwazim bimrim

Dixwazim bigrim

Kurdistana xwe

Axa mîdîya

Translation: “I am Kurdish, stubborn, and iron. Today, the enemy fears me. The smell of gunpowder has fallen on my nose. I want to explode from underneath. I want us to go to the mountains. I don’t want to die; I want to take our Kurdistan, the land of the Medes!”

Ancient Times to Antiquity (10,000 BC to 600 AD)

When considering our origins, the world thinks some of the first significant advances of civilization originated in Mesopotamia and Egypt, with their sustenance of living built off rivers for irrigating farmland, leading to advances in society and culture. However, when studying the archaeology of Kurdistan in particular, there is evidence in the mountains of this region, dating back around 10,000 years ago, of the first steps toward archaeology taken, predating even these two civilizations. One can notice evidence of further innovations in the oldest remains of domesticated animals consisting of pigs and sheep found in Kurdistan, dating back to around 8,000 years ago. This evidence shows the area was the starting point of the domestication of animals. Other evidence dated to this time consists of the remains of millstones, mortars, and pestles, showcasing the further establishment of agriculture in Kurdistan. Developing agricultural technology led to other regional innovations, such as metallurgy and pottery, that would spread throughout the ancient world on top of agriculture.

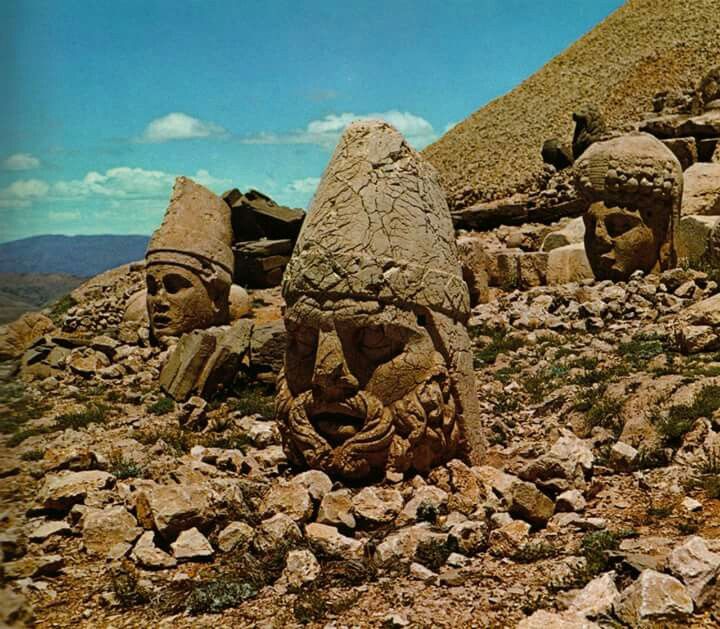

Around 3,000 BC, several kingdoms and city-states in Kurdistan established themselves with great power, even towards the Assyrians. The most notable of these kingdoms are the Manna and Qutil kingdoms. The Qutils were able to unite the kingdoms and city-states of Kurdistan, carrying out invasions towards the Sumerians and the Akkadians and even conquering the region. This power shines from the writings of Naram Sin, the king of Akkadia (2,291-2,255 BC), where he declares how the Qutils acquired the strength to invade him due to the Qutils’ mountainous home. His kingdom fell by the Qutils 5 years after those writings. The Qutil kingdom shows the amount of influence the Kurds had in the region, in addition to possibly contributing to the name of the Kurds. The Babylonians started using the name Qutil to refer to the people who inhabited the mountains of Kurdistan, including the Medes, in 653 BC. This name most likely provides a basis for other titles such as Qardu or Qarduk, similar in etymology to “Kurd.”

The Manna kingdom was unique at the time compared to other domains, such as Mesopotamia, riddled with authoritarian rulers, in that its governance was much more similar to the democracies that are more common today. In an address to Assyria, the king of Manna does not refer to himself alone but also mentions his power is bound to the decisions of others in his kingdom, a multi-body power with equal involvement from its citizens. This plurality of power would continue in the region through realms such as the Adiabenes, the Ayyubids, and other powers further in time.

Despite these technological and political advancements providing the foundation for Kurdish identity, outside influences also seeped into the consciousness and autonomy of the Kurds, with varying effects. This influence began with constant wars waged between Mesopotamia and Kurdistan. The conflict would become a source of loot and enslaved people for the kingdoms, and Kurdistan weakened as a war zone from Mesopotamia’s many victories. The Aryans, a group of Indo-European peoples, would take advantage of this chaos for their interests.

When the Aryans arrived at the mountains of Kurdistan, wars began from 1,200 BC to 900 BC, causing an economic crisis throughout Kurdistan and all of Southwest Asia due to the onslaught carried out towards Kurdistan. On top of this, what was once a unique and thriving Kurdish culture became assimilated under the customs of the Aryans. Kurdish culture succumbed to Indo-European elements, particularly in its language. However, another Aryan group, the Medes, would ensure the further advancement of the Kurds in their influence on other kingdoms. The Medes would unite the Kurds against the Neo-Assyrian Empire between 745 and 606 BC before ultimately defeating the Assyrians by taking control of the capital, Nineveh, in 612 BC. This united force of the region would continue under the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great, which further solidified the Median influence on Kurdish culture, language, and even religion by introducing Zoroastrianism, considered the first religion emphasizing the worship of one God.

However, starting with Alexander the Great defeating the Achaemenid Empire in the 4th century BC, the Kurds lost their former influence between varying empires, from the Romans to the Sassanids. During this time, however, they would still hold ground culturally and politically to varying degrees. There would be times when the Kurds would have some autonomy over their affairs while still living under other empires. This semi-autonomy would even continue into the Middle Ages under the rise of Islam in roughly 600 AD, despite losing their religion, Zoroastrianism, to the Islamization of the Caliphate.

Kurdish Literature and the Events of the 19th and 20th Centuries

Outside of the ability to exert their autonomy with others, another essential characteristic inherent in people groups worldwide is literature. Literature within a culture can carry on particular traditions and inspire a sense of identity among the people to unify them. Whatever part of the United States you grew up in, your schools most likely taught you about the works of Mark Twain or Charles Dickens if you live in Britain. These are authors whose works contributed to the national consciousness of their respective countries, showcasing the cultural practices of their periods and unifying their cultures in these shared experiences. Through literature like this, nations develop and, depending on specific literature, may have inspired particular actions that shape the collective identity among its target audience, including, but not limited to, seeking autonomy.

The Kurds developed a similar quality of literature in their history, even under the Islamic caliphate. During this period, poetry and education in the Kurdish language were quite common in Kurdish courts and Quran schools. This cultural development would develop in the Kurmanji (Northern Kurdish) dialect into the seventeenth century. This period created literary giants among the Kurds, consisting of several historians, scholars, and poets. Of high significance among these authors was the poet Ehmed Xani, who wrote the tragedy of Mem and Zin. The story is similar to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, with two lovers meeting death after failing to marry each other.

Interestingly, at the start of the late nineteenth century, Kurds started to look to the story as a national epic, seeing the story as a metaphor for the tribal ties of the various Kurds blocking the path to the independence of Kurdistan. Although the story most likely began as a simple love poem, this change in interpretation created an awareness of Kurdish identity that would lead to further movements for Kurdish independence in the twentieth century. However, this would only come with the cost of what would occur to the Kurds under the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth century and the events following World War I.

The Ottoman Empire attempted to create a further centralized state in the late nineteenth century. This despotism was due to increased foreign pressure from varying colonial powers, such as Russia and much of Europe, and several separatist movements against the Ottomans. The Ottomans thus limited the rights of people groups within its borders to ensure its authority. As a result, the Ottomans did away with the tribal emirates of the Kurds, belittling any autonomy the Kurds had previously. A decline in Kurdish literature came with this loss of authority in the courts.

While America came out of World War I and into a period of economic prosperity, the Kurds had yet to face the worst. After World War I, the Ottoman Empire collapsed. As a result, the world powers involved in the war established the 1920 Treaty of Sevres to draw the boundaries of the nation-states that would lay claim to the region. Notably, this treaty guaranteed an independent democratic state for the Kurds.

However, establishing the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne broke this promise, giving higher priority to drawing the borders in favor of the Republic of Turkey, a Turkish nation-state succeeding their own Ottoman Empire. After gaining the territory of a fraction of Kurdistan, Turkey criminalized the Kurdish language within Turkish borders in public and private spheres in 1925, even going so far as to abolish centers of Sufi thought where the Kurds attempted to develop their language further. There would even be fights and ethnic cleansing staged against the Kurds in Turkey and the countries of Iraq, Iran, and Syria.

In these countries, the Kurds were prisoners to be humiliated and beaten. The Kurds were targets of these countries’ mass assimilation and terror. The oppressors silenced the voice of Kurdish culture and reduced Kurdish lives to mere dolls, tossing them to the side.

The Mahabad Republic: Dawn of the Kurds

However, the suffering the Kurds endured during this time did not wipe them out of existence or extinguish any hope for autonomy. A tiny spark would erupt into a flame spanning generations after it. A fire burning in the heart of the Kurds, even today, would begin to form the very character of Kurdish resistance. This spark ignited in the Kurdish city of Mahabad, within Iran’s borders.

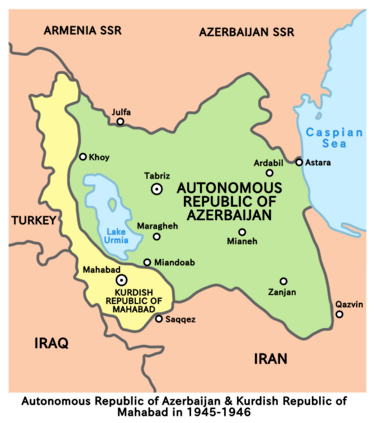

In August 1941, the Allies took over Iran, creating the Tripartite Agreement on January 29, 1942, between Britain, the Soviet Union, and Iran. This agreement ensured that Britain and the Soviet Union would only temporarily occupy Iran for six months, with Iran maintaining its independence. At the same time, it also allowed the Soviet Union to gain control of Northern Iran, which they used to support different minorities as governments within the Soviet Union.

The Mahabad Republic was one of these governments, receiving the backing of the Soviet Union. Its leader was Qazi Muhammad, the founder of the Kurdish Democratic Party of Iran (KDPI), which is still active today. He declared the establishment of the Mahabad Republic in January 1946 and would establish further changes for Kurds that would be significant to future Kurdish movements.

To begin with, several schools under the Republic taught in the Kurdish language. These schools would revive the language development of Kurdish that faded away during the last years of the Ottoman Empire. The Kurdish tongue broke free of history’s chains, and its language flowed into the territory of the Mahabad Republic, with Kurds legally speaking their native language.

Qazi Muhammad also made a point of the advocacy of women in this democratic struggle. He appointed his wife as leader of the Democratic Women’s Union of Eastern Kurdistan and established several schools for girls in the Republic. In a region where women were, and still are, oppressed by patriarchy, these actions served as one of the first steps toward liberating women in the Middle East. Although Muhammad’s government consisted of men, these policies would begin a trend in Kurdish movements towards making women the focal point of their activism.

Despite the achievements created under the Mahabad Republic for the rights of the Kurds, the Republic would only last for close to a year. Iran considered the Soviet support of the Kurds as a threat to its sovereignty. To limit the power of the Mahabad Republic, Iran negotiated with the Soviet Union to allow them control over an oil concession in northern Iran. The Soviet Union agreed to the terms, withdrawing support from the Mahabad Republic in May 1946. Iran would later invade the Mahabad Republic and take it over in December 1946.

The Iranian regime would later execute Qazi Muhammad in the heart of Mahabad on March 30, 1947. Despite this, the execution did not deter Qazi Muhammad’s passion for Kurdish rights. As the regime hung him, his last words were:

“Ultimately, you are achieving nothing. I am dying for the freedom of my people and I am proud of this honorable death. Even at the moment when my body hangs from the rope, my shoes are above my enemies head.”

These words would dart into the Kurdish spirit for years to come. The utmost determination of Muhammad to continue standing for the Kurds, even to the point of death, revived hope for Kurdish autonomy. This spirit would renew the Kurdish struggle time and time again, slowly bringing the Kurds to political standing. The flame of liberty’s torch shone high, with Qazi Muhammad passing it on to others who would continue the struggle.

Consecutive Kurdish Movements

In the wake of the Mahabad Republic’s fall, two major Kurdish movements followed, one in the borders of Iraq and the other in Turkey’s borders: the movements of the Kurdish Democratic Party (KDP) and the Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK).

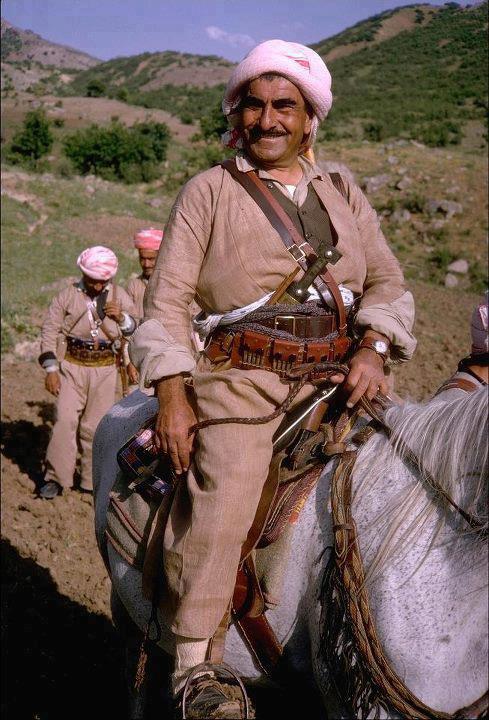

The KDP was a continuation of Qazi Muhammad’s KDPI by Mustafa Barzani, one of the former generals of the Mahabad Republic. After the Mahabad Republic’s collapse, Mustafa Barzani fled Iran with his followers and resumed revolutionary activities of the party in Iraq with armed resistance against Saddam Hussein. After a decade of conflict from the 1960s to the 1970s, Mustafa Barzani attempted negotiations with Iraq, Iran, and the United States.

The purpose of these negotiations was to establish peace for the Kurds in Iraq’s borders and, at other times, for support in fighting against whoever was targeting the Kurds, most notably U.S. support when attempts to negotiate with Hussein only led to more conflict. Unfortunately, these powers would betray the Kurds and leave them to their demise or carry it out. The United States, in particular, withdrew support from the Kurds to gain better relations with Iran and Iraq during the war between them in 1975, leading Mustafa and some of his men to flee again into exile due to losing their ability to fight for their rights in Iraq. His son, Massoud Barzani, would later take leadership of the KDP, and Jalal Talabani, a leader in the Kurdish movement, formed the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), a party similar in scope and aims to the KDP.

The following 15 years would consist of hardship unknown to the Kurds until then. As revenge for the KDP’s alliances with Iran and the United States, Saddam Hussein began the Anfal campaign, a pogrom of ethnic cleansing of Kurds, other ethnicities, and others who opposed his power. The Iraqi government indiscriminately slaughtered thousands of Kurds, the tragedies of post-World War I returning to haunt them. The campaign culminated in the Halabja massacre, where he used nerve gas bombing to decimate the town.

Thankfully, in the 90s, the United States and other powers established a no-fly zone over Southern Kurdistan in Iraq, paving the way for the Kurdish movement to create the Kurdistan Regional Government, which still exists today within the federalist Iraqi government.

The Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) would not get the same support from the United States. At its creation, the oppressive measures towards Kurds in Turkey from the nation’s founding were still in effect, and the state still demanded the assimilation of Kurds into Turkish culture. As a result, when the PKK began its armed insurgency in 1984, Turkey considered it a terrorist group. Western allies, including the United States, labeled it likewise, still keeping this status today along with Turkey.

The main reason Western countries listed the PKK as a terrorist group was Turkey’s ties with them through NATO or the North Atlantic Trade Organization. This alliance is a bloc that the West made against the Soviet Union for cohesion against them. Since Turkey is a member of this alliance, the West maintains the PKK’s status as a terrorist group to keep close ties to Turkey. Despite this, its status as a terrorist group does not mean the PKK has had little impact on the Kurdish movement. On the contrary, the group has made ideological contributions to the Kurdish movement that are experimented with today.

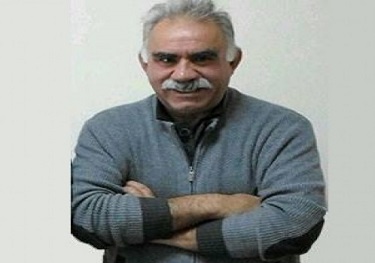

When Abdullah Ocalan founded the PKK in 1977 with close friends of his, it began as a Marxist Leninist group with a centralized authority surrounding Ocalan. It would then start an armed insurgency against Turkey in 1984 in response to repressive measures towards the Kurds, aimed at establishing a Marxist-Leninist state for the Kurds. Over time, Ocalan changed the group’s goals to simply seeking autonomy within the Turkish state for the Kurds. After the Turkish state captured Ocalan in 1999, his political thought would further change in prison, where he read the libertarian socialist ideas of Murray Bookchin to propose a new ideology for the PKK called democratic confederalism.

Democratic confederalism is what would be considered grassroots democracy. This philosophy is a political ideology where rather than democracy implemented in a government where you vote for a leader to carry out government functions you wish to see, it starts with individuals carrying out tasks usually assigned to a government. Institutions under democratic confederalism aim to ensure the rights and power of all groups involved, starting from the individual to the family, then neighborhoods, towns, and so on. Everyone in these groups would have an equal say in all matters of their communities, appointing representatives to meet with others to discuss the decisions of the groups involved.

How this ideology will affect Ocalan’s authority is paramount. Due to the ideology’s aims of decentralized control, Ocalan will possibly not be the center of power for this movement if he achieves freedom from prison. Additionally, democratic confederalism also aims at giving cultural rights to other ethnicities within their communities, equal to the rights Ocalan says he wants for the Kurds.

These developments beg the question: Why did Abdullah Ocalan choose policies that risk his authority? What caused him to give up a nation-state model in favor of autonomy under the Turkish Republic?

One factor to consider was the difficulties surmounted by armed conflict with the Turkish state. Ocalan’s forces were spread thin, too weak to continue armed resistance. His armed resistance also gave a negative image towards the Kurdish movement within Turkey’s borders, considering the West’s listing of PKK as a terrorist group.

Although the PKK is still armed today, this transition to an ideology more open to negotiations with Turkey has improved its image. Abdullah Ocalan’s image is in the same light as Nelson Mandela, a former imprisoned freedom fighter who was eventually released and achieved the end of apartheid in South Africa for Africans through peaceful means. The decisions have also, to some extent, decreased confrontations with Turkey, with occasional armed skirmishes still occurring.

Abdullah Ocalan gave another reason for this change in his book, Manifesto for a Democratic Civilization (Volume I). In the introduction of his book, when he is discussing the reasons for his trips to different countries before his capture, Ocalan states his reasoning with the following:

“My three-month peregrination between Athens, Moscow, and Rome was not without value, though. This adventure led me to understand the essence of capitalist modernity- the basis on which this defense is built- despite its many masks and disguises. If not for this insight, I would either have been a primitive nationalist aspiring for a nation-state, or I would have ended up in a classical left-wing movement. Thus, my change in thought and policy can be ascribed to this forced adventure.”

Regardless of whether his political ideology is correct, his statement shows a moment of introspection Ocalan had. If his words are truthful, Ocalan realized there were holes in his aspiration for a Marxist-Leninist state, on top of ways that democracy should progress in this day and age. This statement shows an ideological motivation in his decisions instead of only practical ones, such as survival or gaining influence.

Today’s Achievements and the Future

The Kurdish movement continues to make achievements for Kurds in the Middle East. The most notable political movements among the Kurds are the regions where they have the most autonomy: the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in northern Iraq and the People’s Democratic Union (PYD) in Northern Syria, or Rojava as the Kurds call it.

Since the United States established the no-fly zone over Bashur in the 90s, the KRG has developed into Iraq’s critical economic sector. The region has become a sight of several business ventures. A notable example is the Kurdish Asiacell, Iraq’s first mobile telecommunications company, with over 10 million customers. It is the source of 97 percent of the population’s mobile connection and is now a public icon in the country and abroad. The region’s achievements are also evident in other ways, such as being the place of one of the lowest tax rates in the world and women not being required to veil in public.

Meanwhile, the PYD is implementing Ocalan’s ideas of democratic confederalism within the borders of their region. It is not just considering the Kurdish question with its ideology but the rights of other groups and ethnicities. The administration ensures that women are also involved in leadership, in addition to each of the ethnicities and groups in the PYD, such as Christians and Arabs.

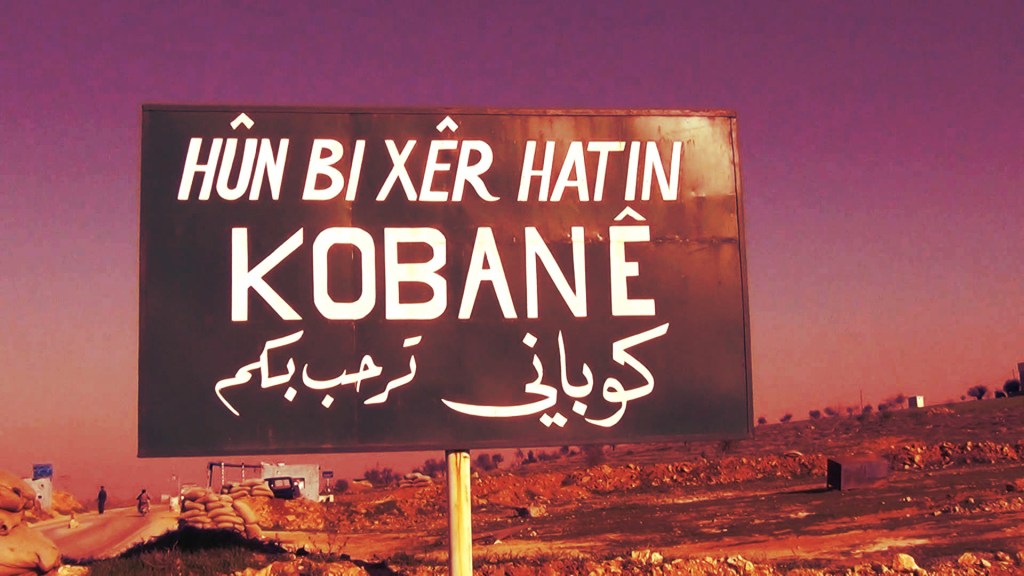

Both regions also contributed heavily to the fight against the Islamic State throughout the last decade and continue to do so today. The PYD, with their People’s Protection Units (YPG), liberated the city of Kobane from the Islamic State, in addition to the whole of Northern Syria. They also rescued the Yazidis, a Kurdish-speaking religious minority in northern Iraq, when the Islamic State committed genocide towards the Yazidis. The KRG has taken in refugees from ISIS’s onslaught and continues to do so today from other conflicts. They also sent Peshmerga troops to Kobane to aid the Kurds in Rojava.

Despite these achievements, the future of the Kurds faces uncertainty in their movements. The Turkish Republic took the city of Efrin from the PYD in their Operation Olive Branch in March 2018. The Turks have appointed pro-Turkish factions as de-facto rulers of the region. The groups subject the citizens to forced displacement and kidnappings. Where many Kurds once lived before this, now the occupation forces are moving Turkmen and Arabs into formerly Kurdish homes. The occupation has increased Turkey’s presence in Rojava, creating threats to the sovereignty of the populace.

Meanwhile, in the Kurdistan Regional Government, the administration held a referendum in 2017 to declare an independent state of Kurdistan in Bashur. Despite 90 percent of the votes favoring independence, the countries of Iraq, Iran, and Turkey did not approve of it. Iraq ultimately did not rule it, stating it was “unconstitutional,” burning the opportunity for independence to cinder. Additionally, the Kurds lost control of the oil-rich city of Kirkuk from Iraqi forces after the referendum. The Kurds there say they now cannot celebrate their cultural events due to pressure from Iraqi authorities.

Even with these challenges and the bit of autonomy the Kurds have, they continue to carry on the spirit of their ancestors. The Qutils’ strength towards Mesopotamia still shines in the Kurdish struggle against the Islamic State and other oppressors today. The economic progress of the KRG mirrors the innovations of agriculture introduced in Kurdistan throughout antiquity. Qazi Muhammad rests easier in his grave than during the aftermath of the Mahabad Republic’s fall, with Kurdish culture still progressing today under the new movements. Despite challenges to their rights, the Kurds maintain a will of iron, stubborn against any steps towards their destruction.

All these achievements give the Kurds a leg to stand on in the world. But only a leg! Even with foreign aid and a heightened awareness of their existence worldwide, the Kurds are still on their own. They continue working hard to make themselves relevant to others for their rights, only to be cast aside in another instance. A news media outlet in our cultural spheres might write about them occasionally, only to move on to something meaningful for their nation’s audience rather than making known what the Kurds think about themselves. As a Kurdish commander in the YPG, Adam Derike stated during the more intensive periods of the fight against ISIS:

“The Islamic State is fighting humanity. We take our orders from the people, and we are fighting for humanity… But all the time, if you are fighting for humanity, you are fighting alone.”

The Kurds are an example of why people different from us are worthy of our attention. And what is at stake if it’s not received.

Sources

Asoya Helbesta Kurdî. (n.d.). Cegerxwîn – Kîme EZ. Asoya Helbesta Kurdî. https://www.helbestakurdi.com/helbest/cegerxwin–kime-ez.html

Azeez, H. (2023, August 9). An enduring legacy: The Republic of Mahabad & Qazi Muhammad. The Kurdish Center for Studies. https://nlka.net/eng/the-enduring-legacy-of-the-republic-of-mahabad-and-qazi-muhammad/

Bengio, O. (2017). Iran’s Forgotten Kurds. In Kurds in a volatile Middle East (pp. 33–37). essay, Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep04759.9?typeAccessWorkflow=login&seq=1.

Glavin, T. (2015). NO FRIENDS BUT THE MOUNTAINS: The Fate of the Kurds. World Affairs, 177(6), 57–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43555270?typeAccessWorkflow=login

Gunter, M. M. (2000). The continuing Kurdish problem in Turkey after O¨Calan’s capture. Third World Quarterly, 21(5), 849–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/713701074

Itzchakov, D. (2017). The Historical Backdrop. In Conflicting interests: Tehran and the national aspirations of the Iraqi Kurds (pp. 7–9). essay, Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep16824.5?typeAccessWorkflow=login&seq=4.

Izady, M. (1992). History. In Kurds: A Concise Handbook (pp. 23–41). essay, Taylor & F., U.S. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://archive.org/details/kurdsconcisehan00izad/page/n5/mode/2up?view=theater.

Krajeski, J. (2015). What the Kurds Want: Syrian Kurds are trying to build a leftist revolution in the midst of a civil war. Is it a new Middle East, or just another fracture? The Virginia Quarterly Review, 91(4), 86–105. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44714253?typeAccessWorkflow=login

Leezenberg, M. (2023). History, culture and politics of the Kurds: A short overview. Kulturní Studia, 2023(1), 115–127. https://doi.org/10.7160/ks.2023.200105

Mansfield, S. (2014). The Genius of the Kurds. In The miracle of the Kurds: A remarkable story of hope reborn in Northern Iraq (pp. 199–206). essay, Worthy.

Öcalan, A. (2020). The Sociology of Freedom: Manifesto of the Democratic Civilization, volume III (Vol. 3, Ser. Manifesto of the Democratic Civilization). PM Press.

Öcalan, A., & Guneser, H. (2015). Introduction. In Manifesto for a Democratic civilization. the age of masked gods and disguised Kings (Vol. 1, Ser. Manifesto for the Democratic Civilization, p. 23). introduction, New Compass Press. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://archive.org/details/manifestofordemo0000cala/page/22/mode/2up?view=theater.

Puttick, M., Al-Kaisi, Y., & Bilikhodze, M. (2020, July). Cultivating Chaos: Afrin after Operation Olive Branch. London, England; Ceasefire Center for Civilian Rights.

Rubin, M. (2016). Who Are the Kurds. In Kurdistan rising?: Considerations for Kurds, their neighbors, and the region (pp. 12–18). essay, American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03254.4?typeAccessWorkflow=login&seq=14.

Rudaw. (2023, September 25). Kurdish leaders commemorate independence referendum on sixth anniversary. Rudaw.net. https://www.rudaw.net/english/kurdistan/25092023

Leave a comment