DISCLAIMER: ANY VIEWS COMMUNICATED BY THE INTERVIEWEE ARE THEIR OWN

Where to Belong

It’s natural to feel an attachment to where someone grew up. We spend much of our lives there, with many vital aspects of our personalities, from the connections we made to our experiences in school, forming in nearly every period of existence. It’s where we learn how to be human and exist in this world with the people around us, creating a sense of belonging to our homes that inspires nostalgia as time goes on for the times that once were.

It is even more compelling to feel an attachment to foreign places that also help us grow. Exposure to new experiences shows us something about ourselves that we never knew about before or gives us opportunities we might not have had at home. We might be amazed at the hospitality of the new culture or might come across new ideas that cause us to reorient our lives in ways we never thought of. The experience could be so rewarding that it even warrants establishing another place as a home away from home!

Dilovan Perwer’s time in the US military inspired such a sentiment within him. A soldier of Kurdish ethnicity who served in the US military during the Iraq War, Dilovan saw US support for the Kurds there as a massive influence to helping his nation establish semi-autonomy in Iraq as the Kurdistan Regional Government, making him proud to be Kurdish while also identifying very strongly with another country he served. His interview shed further light on how his time in the military led him to form this view and how it affected his life in the following years.

Work as a Translator

“When the US fought the Ba’ath Regime, the Kurds could pass freely in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) without having to go through background checks. It became a safe and beautiful place. We became the 51st state of America! Our connections with them gave us peace!”

Dilovan laughed and continued. “I’m American! I’ve been in this country for 28 or 29 years. It’s a big part of my life! I’ve been in this country for half my life, and I’m proud to say this!”

Dilovan Perwer came to the United States from Northern Kurdistan (Bakur), within the borders of Southeastern Turkey. Afterward, he became a Kurdish-to-English translator for the American army in 2003 when they started fighting the Ba’ath Regime. He served as a translator in the KRG, primarily around the Iraqi-Turkish border until around 2012 and is now retired from the workforce. He’s also a HAM Radio enthusiast and the first Kurd in the US to receive his license to operate a HAM Radio Station in the country.

“In the United States, I wasn’t doing anything at first. Then, the American Army came by and said they needed a translator. The men told me to contact them for more information if I was interested. I came to them and said I wanted to help, and then the Army gave me training and sent me to Germany for six months. I then returned to America briefly before being sent to Kurdistan as a translator.

“I was given a background check at Washington DC. Once they saw that all of my information was correct and I was clean, they sent me to Kurdistan.” He smiled briefly. “They saw I wasn’t a problem and were ready to send me there!”

A lot happened during the Iraq War while you were there. What happened while you were a translator in Kurdistan?

“When I came, it was very intense. I saw many things. At first, we were very nervous because the Ba’ath Army was launching RPG rockets into Kurdistan. We weren’t sure what would happen. We settled down once the US drew the Green Line from Mosul to Duhok and other places. It became very peaceful! We could pass through areas of Kurdistan without security checks or any significant threats. We went to the public places in the cities freely!”

A Green Line?

“Yes, they drew a Green Line at Mosul to increase regional security. Once the US established it, it calmed our nerves! We now had security inside. It gave us a lot of hope!”

So when the US drew the Green Line, you saw more peace in Kurdistan.

“Exactly! It was also when the Americans and Kurds started to interact more. We exchanged information and supplies. We were gaining strength in our cooperation! These exchanges were where I started translating from Kurdish to English more often.”

Was there ever a time when you fought against Ba’ath soldiers?

“No, because the fighting with them was further from where the military stationed me. I was in Kurdistan, on the border with Turkey, and didn’t know Arabic, so they didn’t send me outside of there. There were other Kurds who knew more Arabic than I did, and they ventured there, but the military didn’t send me there due to my lack of fluency in Arabic.”

So, there wasn’t a time when you encountered Ba’ath soldiers.

“No, not the Ba’ath soldiers; they were far from me.”

You mainly were with Kurds, then.

“That’s what I was there for. I knew Kurdish but not Arabic, so I worked with Kurds and not Ba’ath soldiers. I also translated for Turks (I know Turkish, too) at the border (Iraq-Turkey border) and translated for the US Special Forces, so my job took me elsewhere!”

Then, you didn’t see a lot of fighting.

“Yes, I was a translator, so I didn’t fight often.”

Childhood

Could you tell me more about your childhood or what it was like growing up?

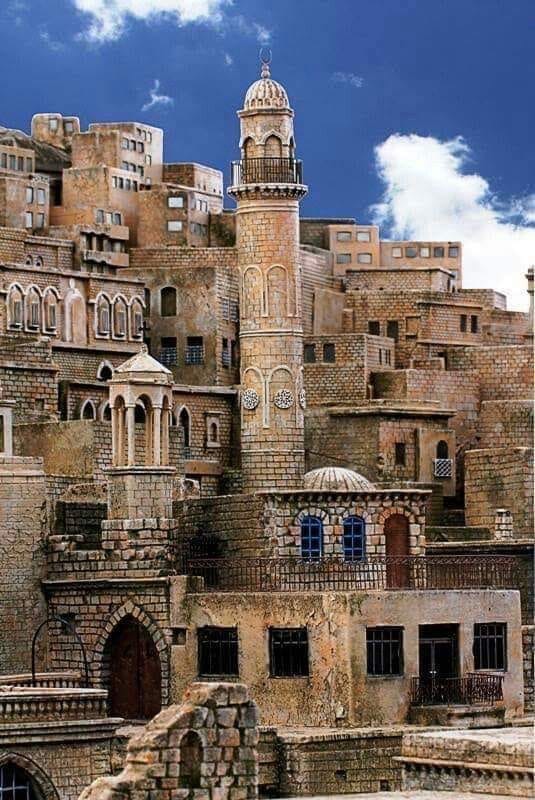

“I grew up in the city of Merdîn. Whenever I was among a group of children, my father would call me ‘Golikê Bej.’ It’s an old Kurdish proverb! We use this phrase to refer to a baby cow with a white spot on it. For example, when there’s a large group of cows, maybe one hundred or two hundred, if they saw a cow with a white spot on it, they’d shout, ‘Golikê Bej!’ So when I was with other kids, my dad would call me this because I stood out among other children. Among a large group of kids, maybe one hundred, thirty, or twenty, everyone knew me! I was important! People would look at me because I did things differently, so my father called me ‘Golikê Bej!’

“I also worked with electronics a lot, just to see what they did. My friends and I would fight with each other a lot, but we also played some! These experiences made up my childhood in Merdîn, Diyarbekir, too! Both places!”

What are some of your memories of Diyarbekir?

“I don’t remember a lot from there. One memory comes to mind, though. One time, while walking in the city in the morning, some people I didn’t know approached me and invited me to a church dedicated to Mary. I decided to come, so they brought me there, and then they brought me in front of the Pope, and he put his hands on my head to give me a blessing, saying, ‘God keep you,’ and then told me, ‘Come tomorrow, and I will show you the path to righteousness.’”

So this was at a church?

“In Diyarbekir, yes!”

So you were Christian?

“No, I was just really young, and they brought me there to tell me all that. They just blessed me, and that was it. They were just some foreigners I didn’t know.”

Missionaries?

“Maybe, I don’t know.”

So they blessed you, but you were young.

“Yes, I was nine years old, haha! Just blessed me on the spot!”

He continued with other memories. “I did other things, too. I played football (soccer) a lot and Gogê.”

What’s Gogê?

“Gogê’s our name for golf. It was just what we called it!”

You talked about your experiences with Christianity. Have you had any other experiences with religion?

“No, I didn’t. I grew up Muslim, but as I got older, I started to research different religions. Once I started to get a larger picture of what was out there, I concluded that I respect all religions, but ultimately, I follow my heart!”

Meaning?

“I believe in myself! I have nothing against religion, but trust that wherever my heart guides me, I’ll be on the right path!”

When we’ve talked before, you’ve often discussed how Kurdistan is important to you. When did you start to develop a solid connection to your homeland?

“My family instilled these values into me. We would read Cegerxwîn’s poetry, and much of our Kurdish pride developed from this. This Kurdishness was the atmosphere I grew up in! My family taught me to value my Kurdish identity and to represent my people!

“Coming to America helped me dive deeper into my Kurdish identity because I could listen to the Voice of America broadcast in my language there! They would broadcast it from Washington, DC, and I’d listen to them on my shortwave radio. You can find content from Voice of America on the internet now! Like on Facebook!”

What year did you start to listen to them?

“In ‘92! They would air a morning broadcast for around half an hour to an hour, and I would listen to them then.”

He continued to mention how much school he had done: “I finished everything from elementary to high school and then came to the United States.”

Did you study at a university before coming here?

“No, I came here as soon as I finished high school. I came in ‘95.”

How did you learn English?

“I taught myself English in Kurdistan. I focused a lot on English grammar, particularly all the different sounds of the language. For instance, ‘ch’ makes a ‘-cheh’ sound, like in ‘chair,’ but other times it makes other sounds, like ‘-sheh’ in ‘Chevrolet’ or ‘-keh!’ in ‘chemical.’ It’s just one set of letters making so many different sounds! I was very frustrated with this. So it became a big focus for me when I was learning English, like the sounds for ‘kn-’ being silent, like in ‘knife’ or ‘knee.’ I focused a lot on contradictions like this!

“Other things were also a big focus for me, like proverbs. ‘I’ll scratch my back, you scratch mine,’ or ‘My way or the highway,’ stuff like that! I would translate the proverbs into Kurdish in my head and repeat them repeatedly until I memorized them. I’d listen to them over and over! I took a class in Nashville as well! I attended an English class for six months when I came here, which also greatly helped me!”

Rights to Language

“When I started school, I didn’t know Turkish. The schools only taught in Turkish, so I had a hard time initially.”

In Turkey, the government represses any form of Kurdish expression. Part of these measures includes making Turkish the dominant language of school lessons. Dilovan discussed his experiences in school and how his Kurdish identity played into them.

“When we went into the schools, it was hard for all Kurds. We didn’t get a chance to learn our mothers’ language completely. Turkish was the only language allowed in the schools, so at home, we spoke Kurdish, but in the schools, it was Turkish. We became two separate peoples, neither one complementing the other… They were forcing us to assimilate!”

Because your language was illegal?

“Yes, exactly! The teachers were Turkish; they weren’t from Kurdistan. So, if you spoke Kurdish, they would beat you and say, ‘You speak Kurdish, but in school, we speak Turkish. Speak Turkish!’ But we didn’t know Turkish, so what could we do? If we spoke Kurdish, we got beaten!”

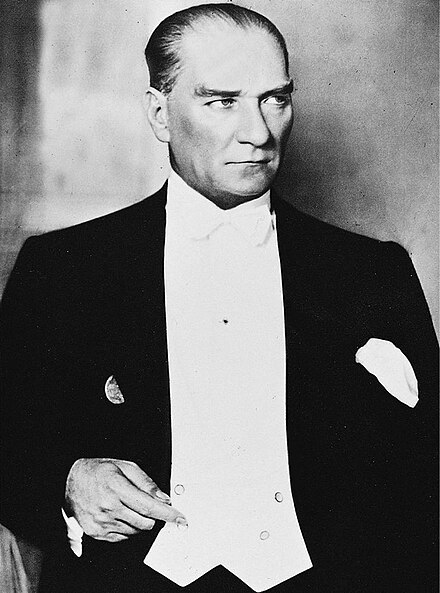

I remember Ataturk (the founder of the Republic of Turkey) saying, “How happy is the one who says I am a Turk.”

“Yes, Turks feel that way, but not us! Turks can say that about themselves, but me I’m Kurdish! Why would my heart be glad to say I’m Turkish? I say my heart’s glad when I say I’m Kurdish, a Kurdish American! Why? Because here, I can speak my language freely, and America acknowledges that I exist! In Turkey, my language is unknown; it doesn’t appear in any of their official records. They say I don’t exist! My language is dead to them! For someone like that, I say, ‘Well, I don’t know you!’ Hah!”

Yes, even if you look up Kurdish videos on YouTube, if there are only automatic captions available, they’re only in Turkish. This option is despite the footage being Kurdish!

“Yes, it’s like this, but I will not speak Turkish. I will speak Kurdish!”

What do you think about the status of your language in the United States?

“The government hasn’t done very much for our language. You know how when you go into the airport, and after they stamp your passport, there’s that sign that says ‘Welcome!’ in different languages? I want the sign to include, ‘Bi xêr hatî!’ You know, my language! I want the U.S. to include my language among them as well! It would also be great if Voice of America did something in the United States for the Kurdish language, too. They broadcast very much in other countries, but I want them to do something here.

“America has helped us, though! They declared March 21 the official day of Newroz (Kurdish New Year), and I have a lot of respect for them because of that. If you work for the government and you happen to be Kurdish, on that day, the government gives you extra money just for being Kurdish! There’s just more that they could do. Many Kurds in Nashville want the schools to have classes that teach Kurdish, ones run by volunteers. However, there was a time when MTSU (Middle Tennessee State University) had a Kurdish class. There were a lot of Kurdish students there, and many American students started to develop an interest in Kurdish culture from encountering them. They started to want to learn Kurdish! So, a friend of mine who was a professor, I can’t remember his name now, had started a Kurdish class there. It was great! It’s not available now, though.”

Other Experiences and Final Thoughts

What was your most significant memory from your time in the military?

“One memory sticks out for me. One day, the captain of my unit sent me to the KRG border with Turkey. He told me, ‘Mr. Dilovan, you need to bring a Turkish commander to us so we can meet with him. Give him this letter at the border and bring him here.’ So I went there on my motorcycle, a Gator, and reached the border, but the commander wouldn’t come out from his post to greet me. I rode my motorcycle towards him, stopped where he was, and asked, ‘Why didn’t you come to me?’

“Now, there was a Kurdish flag at the border. The commander said nothing about the colors but looked at it and said, ‘The flag’s… material bothers me.’ He didn’t want to go under the flag! I couldn’t get him to come because he didn’t want to cross the border under the Kurdish flag! So, when I returned and brought it up with my superiors, they told me, ‘It’s fine if he doesn’t want to come; let him stay,’ and that was it! This memory was crucial for me!”

Because it reminded you of the new autonomy of Kurdistan?

“Yes, my homeland became free, and he didn’t want to acknowledge it! This moment became my life! I have great pride in the Kurdish flag!”

What was difficult for you when you came to the United States?

“I didn’t have a lot of difficulties when I came. The Kurds here helped me if I needed anything, and this happened so, so much! I was very grateful for them! I still needed to learn more English, though, and I knew enough to get by. Getting my citizenship also wasn’t very difficult. I got citizenship five years after arriving, and I’ve lived in America as a citizen ever since!”

At this time, were many Kurds from Bakur (Northern Kurdistan, Southeastern Turkey) in Nashville?

“No, just students or those that came with their spouses. I was one of the few from there that managed to get here. I got my Green Card in a lottery for an opportunity to come here, so I was lucky! Not many Kurds from Bakur came here.”

The Bashuri (Southern Kurdistan, Northern Iraq) Kurds were very kind to you when you came to Nashville. Did any of them ever have problems that you were from Bakur?

“No, everyone was extremely helpful to me! Politics tends to tie us up in knots, but they put that aside for me. I’m grateful for their hospitality!”

As you’ve seen, when the U.S. fought the Ba’ath Regime, this invasion helped the Kurds gain autonomy for themselves. At the same time, however, the United States is allied with Turkey through NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) for military efforts, and the Turkish government persecutes the Kurds in its policies. As someone who’s Kurdish but who also served in the U.S. military, how do you feel about the United States’ relationship with Turkey?

“This is true. America and Turkey cooperate for political interests and are allies. However, the soldiers in the US military thought differently from the government. The US Special Forces were in Iraq during my time there, and I even worked with them a lot. Their general, General David Petraeus, made it a priority not to fight the Kurds, even from the PKK (Kurdistan Workers Party, blacklisted as a terrorist group). Turkey pushed hard for this. They wanted us to fight the PKK, saying, ‘They’re terrorists, they’re a threat to the region, fight them!’ We didn’t take them up on it, though. The Special Forces would say, ‘They might be your enemies, but they’re not ours. We’re not fighting them.’ So, although I don’t like the political situation with the US forming ties with Turkey, I separate that from my experiences in the military. They support the Kurds a lot!

“I witnessed this first hand when translating for the Special Forces. We’d get a lot of PKK guerillas crossing the border, and I’d translate what they said to the Special Forces. Many times, the Special Forces would say to them, ‘We have nothing against you, but you can’t fight in Iraq right now. We’ll let you fight in Turkey, but Iraq’s our territory right now.’ Then they’d let them go, and that would be it! We were generally on good terms with them!”

So, the PKK being in Iraq was a problem for the Turks but not for the US military?

“The military would tell the US government such! They told them they didn’t want to fight the PKK there, and the government accepted this. Our generals would say, ‘The Kurds aren’t our enemies; they’re our friends. We have a strong respect for them! We won’t fight them.’ They always supported the Kurds! The Turks didn’t like this, though.”

During your time there, the Kurdistan Regional Government underwent many developments, such as in the economy and infrastructure. Did you witness any of these developments yourself?

“No, I was mainly with the military. I didn’t get to see anything like this too often.”

How do you think your work as a translator helped the Kurds in the Kurdistan Regional Government?

“When I was there, many of the Kurds loved us there! For me, in particular, sometimes I would go to the bazaar and buy something, but then I saw I didn’t have enough money for the purchase. The storekeepers would let me off the hook, saying, ‘Don’t worry! It’s on us!’ They saw me as a representative of the Kurds in the military since I spoke Kurdish and translated for them. I gained a lot of respect from them because of this. They always helped me when I needed it!”

You’ve discussed your time working as a translator for the US military and how important Kurdistan is for you. What is the most important thing from your work and identity for the Kurds?

“I believe anyone who calls themselves Kurdish must speak the Kurdish language. If you can’t speak the language, learn it! This part of Kurdish identity is a big deal for me! With the technology we have now, like the internet and smartphones, it’s so much easier to learn anything that Kurds should be able to pick up their language quicker than before! There are Kurds that say, ‘Well, I’m Kurdish, but I don’t speak the language,’ no! We must speak Kurdish! Think Kurdish, speak Kurdish, let your heart be Kurdish. Our language is our identity! I can’t stress enough how important this is for me!”

This interview proceeded on October 31, 2023.

Leave a comment